The ballad of Lonesome Jim

There aren’t very many machines in my shop that don’t pertain to Porter-Cable in some way. This is by design; it would be hard to accidentally build an all-P.C. workshop. I’ve gathered equipment from virtually every era and product line, replacing the original hodge-podge of vintage machines wherever possible. This isn’t always possible, of course- Porter-Cable didn’t make everything, and where functionality conflicts with verisimilitude, functionality wins.

There are exceptions. I have a Keller power hacksaw that toils away cutting stock for the other metalworking machines, and the only P.C.-ish equivalent is a Lipe-Rollway portable hacksaw that is no match. Similarly, I have a Greenard #3-1/2 arbor press because none of the related companies made anything like it.

Then, there’s Lonesome Jim.

Back in December of 2021, I was looking for a possible milling machine that would be compatible with my Porter-Cable #2 universal milling head. Originally developed for and sold by Whitney Manufacturing Hartford, CT, this head was intended to give older hand millers vertical capability. I had found one for my collection and realized that it could be useful in a supporting role with the Rockwell vertical milling machine I had recently rebuilt. I had a few conditions that any potential milling machine would have to meet, namely a small footprint, an age similar to the universal head, and provision to mount it in place of the overhead arbor support.

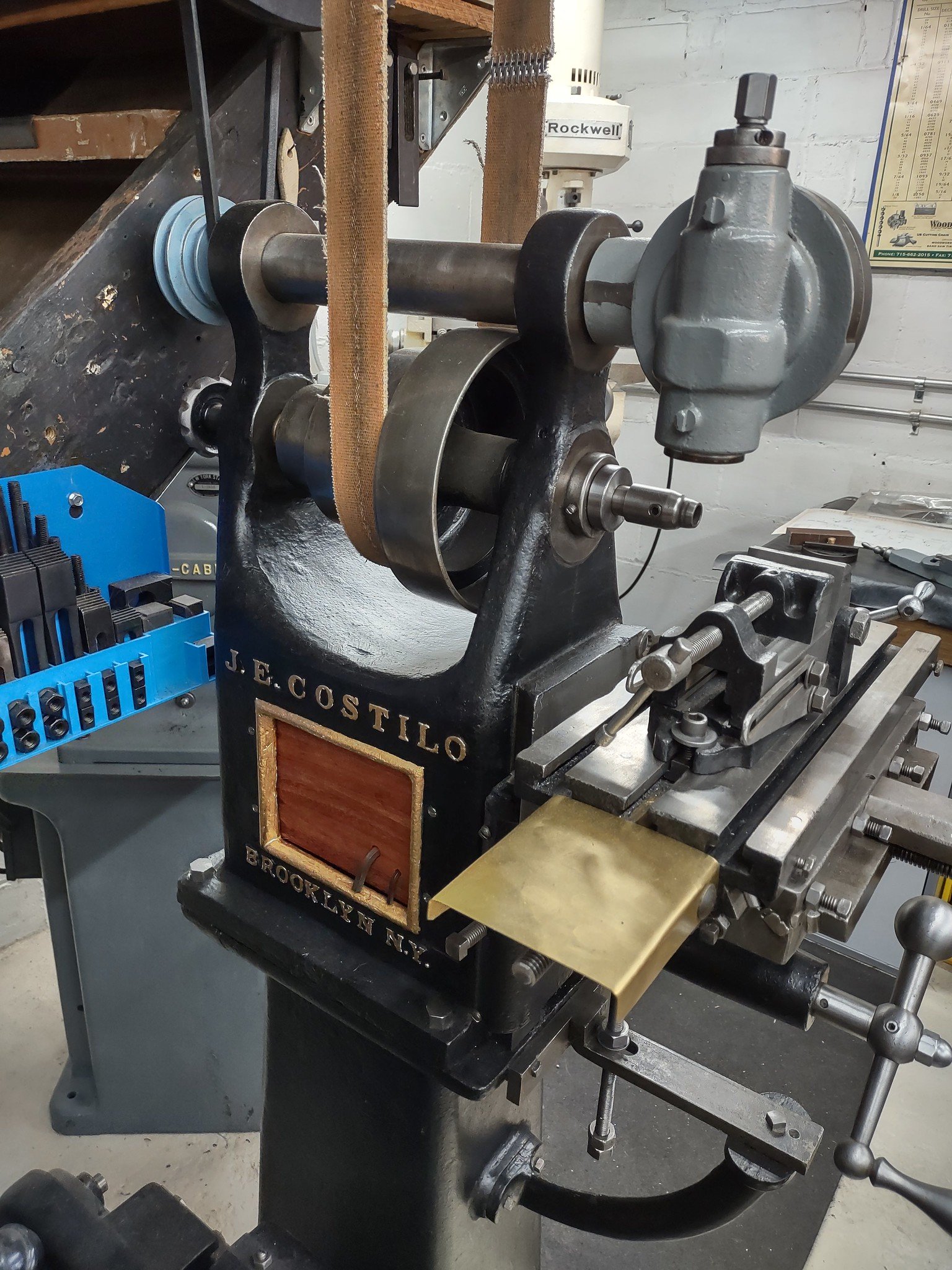

While browsing online for a machine that met the criteria, I found an unfamiliar name at HGR, an industrial surplus dealer near me. I had never heard of the J. E. Costilo Machine Works of Brooklyn, NY, but I was intrigued by the small scale, obvious origin during the lineshaft era, and ( let’s face it) low asking price. For a mere 180.00 and tax, I could add this interesting fellow to the team, and if it didn’t work out, I felt I could always get my money back out of it. A further motive was pity. Some research by myself and others led to the discovery that J.E. Costilo was in business from 1893 to 1901, moving to Manhattan that year before fading into obscurity. The thumbnail in the sales ad was enough to reveal that the machine was in poor shape, missing several parts and badly damaged, which was heartbreaking to see in a machine of that era. When it comes to any kind of tool, I don’t pursue the intact ones, the machines that are in gently used condition. I’m too much of a mechanic for that.

I was able to get confirmation of the overhead support diameter, and it seemed that the machine was the right size. What did I have to lose?

When I first laid eyes on the Costilo, I was drop-jawed at the level of indignities the poor fellow had suffered in the past 120 years. The milling machine had lost the overhead support ( not the world’s biggest deal, but still), and had been converted from a lineshaft machine with the crudely installed, shop made countershaft and motor that was mounted via a series of inaccurately drilled holes through the side of the main casting. Worse, the lead screw for the x-axis was completely torn out of the machine, nut, balanced crank, and all. In its place, some degenerate had mounted an adjustable stop bodged from a piece of all thread and some nuts, while a sub-table kludged together from flat stock and an entire box of 1/4-20 flathead screws was slapped on the original table surface.

There was also good news. I’ll think of it any minute.

I posted bail for the ancient milling machine and loaded it up ( well, the forklift driver loaded it up- the Costilo is a lot heavier than it looks). Once I got home, I spent an hour and a half just removing all the BX cables, hack job guards, and other barnacles slathered haphazardly to the mill by generations of millwrights ( or in this case, millwrongs). To my surprise, the milling machine had suffered an injury that staggered belief- the entire table had been broken in half, the damage “corrected” by brazing the halves back together. In addition, the castings, under all the brackets, were pockmarked with bolt holes.

I love getting machines in this kind of shape, really. You have absolutely nowhere to go but up.

I started by giving the mill a bath. A thorough degreasing/scrubbing/pressure washing peeled most of the vomitous green paint off of the milling machine as if I was shucking a corn cob, and a session of wire wheeling removed what little original paint remained, leaving clean ( if butchered) castings. I stripped the milling machine to the last screw and sent everything off to the vinegar bucket for derusting.

I dragged the main castings into the basement shop and eased the Costilo into its berth, recently vacated by a drill press that I never really used. After filling the holes in the castings with epoxy, I painted the milling machine a slimming satin black. The raised lettering and trim around the openings in the casting got a coat of gold paint. There’s no evidence that the mill originally had an accent color, but after all its suffering the poor thing deserved to be tarted up a bit.

Going through the cleaned hardware, I rejected any and all pieces that were obviously too new to have been original to the mill. Luckily, most of the major components had an assembly number stamped on them; anything marked, “25” was supposed to be there.

After a little work, it became obvious how much was missing from the mill, and how much needed to be made from scratch. This wasn’t a serious problem in and of itself. What was problematic was recreating the original appearance.

See, I didn’t have any idea what the milling machine was supposed to look like.

As of this date, only one catalog cut of a J.E. Costilo machine has come to light, and it isn’t the mill. In fact, no other Costilo machine has surfaced. Our boy here is, at present, the sole survivor of the James Edward Costilo machine Works, hence the moniker, Lonesome Jim.

It’s not all bad news, though. There are a number of similar machines to extrapolate from, the closest being a Carter and Hakes hand milling machine. After some studying, I was able to reverse engineer what I think is the most likely configuration. The damaged table was re-repaired by driving bolts into the sea of holes left by the sub-table, cutting them off flush, and cleaning up the whole casting on the surface grinder. There are a couple of major blowouts to be avoided when clamping work, but this is usually not an issue.

The Costilo uses a “rise and fall” mechanism for the Z-axis; the large crank on the front operates a rack and pinion which lowers the table against spring pressure, and relating the hand crank returns the table to operating height. This design lends itself to operations like keyway cutting, a task at which the Costilo excels.

The countershaft was reconstructed and married to a 1/2hp Century repulsion induction motor. Reverse is provided by shifting the brush assembly, and the whole shooting match is mounted to the rafters above the mill, returning it to the lineshaft power source it was meant to have.

Tha Porter-Cable universal head? It fits like a glove, giving the Costilo vertical milling properties and giving it the ability to achieve some very complex angles. It is also powered from the countershaft. The clicking of the belt adds a certain something to the experience.

The two “windows” in the main casting were filled with Mahogany and drilled to accept the tools and tooling most commonly used with the mill; the right-hand side houses all the Brown and Sharpe #7 collets, hex wrenches, and even a small boring head. On the left -hand side, there is room for the horizontal arbor tooling, which I don’t have ( it’s #6 Jarno taper, which went out of style when Teddy Roosevelt was president and is understandably hard to come by). These boards also serve to keep dust and swarf from entering the base, making it easier to keep the milling machine relatively clean. The leadscrews are protected by brass covers, because the Costilo has a lot of spoiling due after all the abuse it suffered.

The Costilo has proven to be invaluable to the shop, handling the surprising workload of shaft repairs that I run into. Sure, the Rockwell could do the job, but the Costilo is faster to set up, leaves the Rockwell free for other things, and is a lot of fun to run. I’ve grown very fond of this time traveler that remembers a world before airplanes were invented.

Welcome to the team, old man. It’s good to have you.