Fix bayonets: Porter-Cable's answer to the jig/saber saw

It's been a little while since I've invited anyone down Porter-Cable lane. There are a lot of reasons for that- I've had my hands full with repairs and restorations, working on the shop in order to streamline operations, and trying my best to get the repairs to my elderly F-250 wrapped up for the season. Besides that, I've covered a fair amount of territory already. I mean, we've deep-dived into circular saws, discussed belt sanders at length, covered the finishing sanders, and even took a look at the drills, complete with a comprehensive list of the million or so versions made before Rockwell dropped the ball. What else is there to examine?

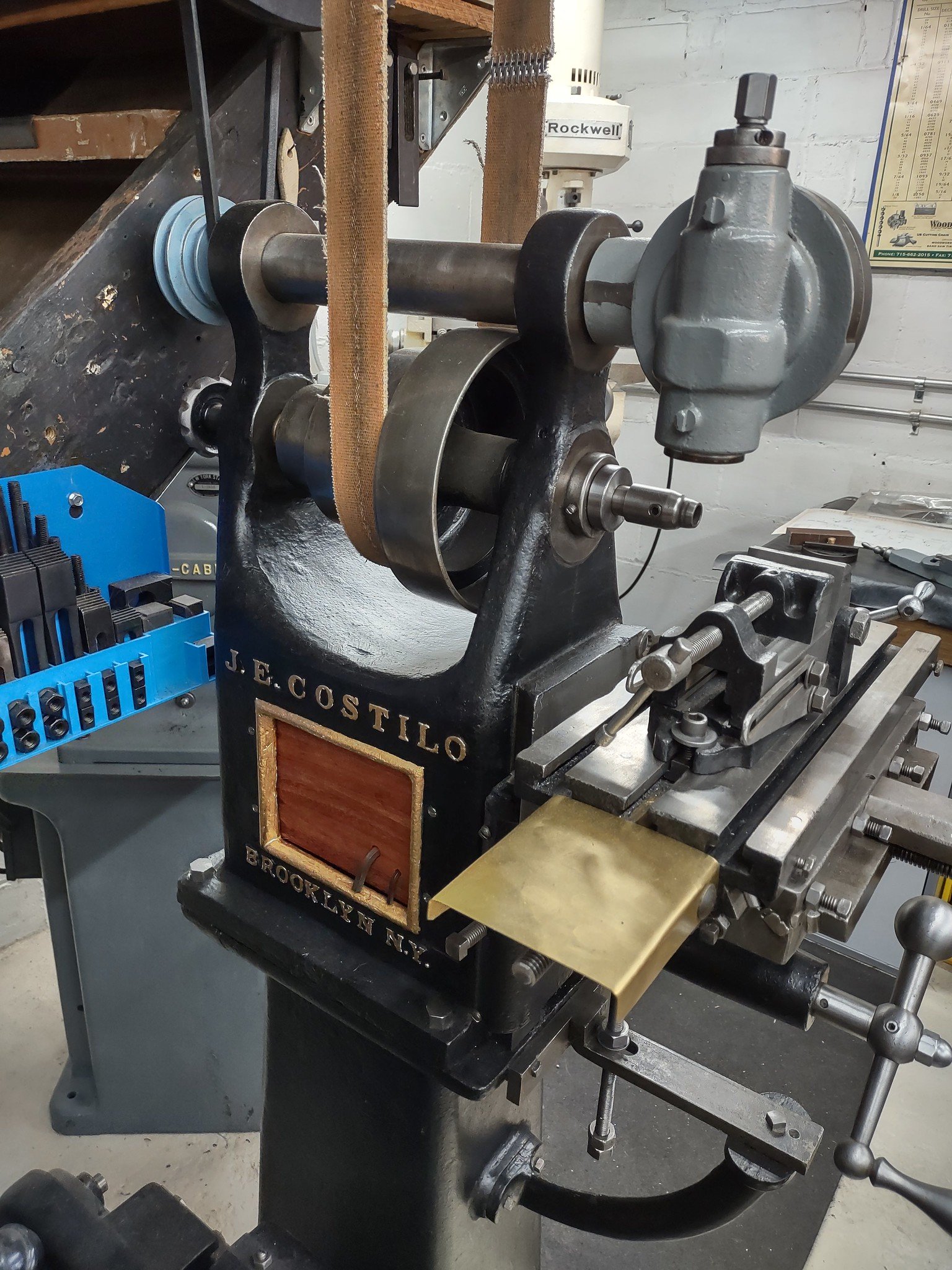

L to R: 148, c. 1955, 152, c.1958, 300, c. 1963, 66, c. 1967, and 348, c. 1966

There are a number of names for the tool we're about to consider; They've been known as jig saws, saber saws, and ( erroneously) scroll saws. Moreover, there were trade names for them, too- the Milwaukee Sawzit springs to mind. But to Porter-Cable ( and later, Rockwell), they were always known as Bayonet saws.

Arguably the best of the breed was the first one out of the gate.

On shelves just in time for Christmas of '55, the 148 was nothing short of a marvel. Weighing only 5 lbs, the mighty 148 is one of the smallest worm-driven tools ever made ( even the equally venerable A-2 belt sander weighed 9lbs). The original version cut at over 4,000 strokes a minute through virtually anything for all the world like Durandal. I own a 148 kit, and I can attest to that fact - cuts in 3/8" steel are well within the abilities of this pocket Hercules. The 148 was built with a fixed base, but an accessory angle-adjusting base was offered from the start. This was a clever design based on the retrofit base created for the first A-6 and A-8 Guildtool saws of the late '40s. The fixed base sounds like a bad idea until you consider the most common use for these saws- they were far and away the most commonly used tool for sink cutouts in the era before laminate trimmers got popular. Both bases could accept the "Magic circle" insert, which fit tightly around the blade and helped prevent chip out. The 148 was an incredibly durable saw with exceptional smoothness and introduced a hitherto unknown concept- it's the first reciprocating power tool to oscillate in the cut, clearing the blade gullets and improving both blade life and cutting speed. It was a truly impressive first try, which was replaced by the 548 by August of 1957.

I'm kidding. While the 548 did replace the 148 in the lineup, there's actually no difference at all save for the number- the change was made to bring the bayonet saw into line with the nomenclature of the late '50s, in which the tools starting with a one were considered Standard Duty, while anything beginning with a five was considered Heavy Duty.

In that vein, another bayonet saw joined the family, and this one retained the " 1" designation.

The 152 was an excellent design in its own right and streets ahead of many a competitor's attempt ( in those days, the only real rivals the 548 had were the Scintilla saws, the Cutawl, and the Black and Decker designs. The Scintilla would go on to beget the Bosch series of jigsaws; the Cutawl existed largely in the world of stage set designers and sign makers, and the B&D was made with diminishing returns until Universal blades went out of fashion). The 152 was destined for the home handyman and was correspondingly less expensive ( in 1959 a 548 set you back 99.50, while it only cost 54.95 for the 152 ), the savings in cost coming from the bevel gear drive system, liberal use of bushings, and simplified construction. This led to a larger machine, and if I were to lay any true criticism at the 152's door, it's the bulkiness of the saw. The angle-adjusting base could be fitted to this saw as well.

Status Quo was held thus until 1962 when the 152 was sent to a nice farm upstate, and the new kid in town showed up.

The 300 looks strikingly like the 152, and there's a good reason for that; it's essentially a 152 on stilts. The mechanism of the 300 is similar to the 152 save for the longer drive link, which increases the stroke by 1/4". This explains the easiest difference to spot between models, as the 300 has a large excrescence in the handle cover, the better to accommodate the link. Another change was the fitting of an adjustable base from standard, a base that also incorporated a rip/circle guide. I'm not wild about the 300 if I'm honest. The longer stroke is a nice feature, but the rather lax job of cramming a longer link in a design that was just adequate for the original system led to the 300 being extremely prone to throwing a rod, the tendency of the design to wear prematurely claiming a lot of them and making it one of the less encountered members of the family.

it wasn't until 1966 that the 300 would be replaced by the 348,

which is the first bayonet saw to be built with the drive system in front, rather than beside, the motor. As a result, the 348 is taller but slimmer, and the clamshell design allows for easier assembly and service. Unfortunately, the downside was wear, exacerbated by the typical dust ingestion of all saws of this class, mixing with the grease to make a crude form of MDF and causing the gears and other moving parts to run dry. Early 348s had a clever feature in the form of a light, built into the housing and turned on and off with the motor switch. This actually did good execution, but the incandescent bulb got very hot and tended to break elements. Replacing this bulb was a chore, requiring the saw to be disassembled significantly, and the feature was dropped almost immediately. I sometimes think about retrofitting my 348 with an LED bulb, but that's waaaay down my to-do list since I use the 148 almost exclusively.

The only other saws of the classic era were the 648 and the 60. I don't own a 648 and am in no real hurry to amend that. The 648 has an impressive stroke and speed and is very sturdy, but it suffers from a fatal flaw in my eyes- it's not ambidextrous. The switch is mounted in such a way that it can only be reached by the operator's right index finger and only if the operator has largish hands. The 648 also deviates from the traditional formula by not having a handle- it's gripped by the motor housing, which is a nice idea in theory ( a lower purchase on the tool lends itself to less tipping), but increases operator fatigue since it's harder to firmly grip an object the larger in diameter it gets. For those reasons, the 648 is a bit of a letdown. Also, it's double insulated, which means it's plastic, which means it's kinda ugly.

Speaking of plastic ( and ugly), there's the 60.

I actually like the 60, if I'm honest, because it reminds me strongly of the tiny post-oil embargo cars of the '70s. In essence, the 60 is a 348 stripped of absolutely everything not strictly necessary to the raising and lowering of a bayonet saw blade. Debuting in April of '65, the 60 was a second wave tool of the Green Line, an infamous series of power tools sold by Rockwell and the leading cause of the ultimate sale of both Porter-Cable and Delta to Pentair. The Green Line tools were lower-cost versions of some of the simpler tools in the Rockwell lineup, being made from Cycrolac plastic in beautiful seafoam green ( as an aside, I actually like seafoam green as a color. Maybe it's because I grew up when everything from toasters to station wagons came in that shade). I was recently given one of these saws by some lovely friends of my in-laws, who found it in kit form for a mere five dollars. The saw needed a little TLC from sitting, thorough cleaning and regreasing and the replacement of some very crunchy field leads, putting it back to rights. The saw cuts well and doesn't really have any serious flaws save for the peculiar pinch bolt design for retaining the rip guide. In a home shop, this saw would probably handle moderate use for decades, as it obviously has. The earliest Green Line tools were not at all poorly made, and the 60 is no exception; while I doubt I'll be using this saw hard, I will put it to work for lighter tasks ( if only to let the little fellow keep his hand in). While the first generation of Green Line tools are adequate, later versions were cheapened up until the number returned to service centers for warranty repair formed literal mounds, as any power tool repairman of a certain age could attest.

There were, of course, other saws made in the '70s, namely the 67/68/69 series. These saws were the basis for all the later post-Rockwell designs that were popular throughout the '90s, even if the original saws were, frankly, awful.

In the end, The last saw standing was the 548. Oh, sure, there were saws with quick-release chucks, but I don't consider any model to be a true bayonet saw unless it uses the L-shank blade interface. Proprietary to Porter-Cable, this design had excellent clamping properties since the shank prevented the blade from being pulled out of a properly tightened chuck. These blades were generally made of a much higher grade of steel than the competitor's offerings and were available in endless permutations and for virtually any material from closed-cell foam to stainless steel. These blades are still frequently seen on *bay, the NOS of 50 years of being more than equal to current demand. I bought heavily of the common styles when they were being discontinued and have enough hundred packs of the widely used ones to keep our boys here in clover for the rest of my life, if not longer.

What happened to these saws? Well, they weren't cheap, for one. A lot of the work they handled became the province of laminate trimmers. Then there's the issue of blades- while Porter-Cable would attempt to make a quick release version, no one really seemed to buy them. I mean, everyone else on the job site had a Bosch, and you could buy blades for those anywhere. What made these P.C. saws so special,

other than build quality, power, speed, smoothness of cut, accuracy, and dependability?

Well, I guess you'll just have to pick one up and see what thousands of woodworkers raved about.

Our Cast:

148/548: 3.5Amp motor, 4,500stroke per minute (idle), 7/16" stroke, 5lbs

152:2.5Amp motor, 4,700 strokes per minute (idle), 5/16" stroke, 7lbs

300:2.5Amp motor, 4,000 strokes per minute (idle), 9/16" stroke, 5lbs

348:3.0Amp motor, 3,500 strokes per minute (idle), 9/16" stroke, 5lbs

60: 2.5Amp motor, 3,300 strokes per minute (idle), 3/8" stroke, 4-1/4lbs

-James Huston

Finishing strong- the story of the Porter-Cable finishing sander

Some time ago, a fellow member approached me about taking a look at a finishing sander, a Porter-Cable 509. At the time, it was determined that the sander was in poor shape. It had three failed pad posts, a counterweight that had long since worked loose and damaged the transmission shaft, and a bodged-together on/off switch that had been poorly soldered into a window hacked into the escutcheon. As the 509 doesn't really share most of those parts with any of the other sanders, I decided that the best move was to dig out a Porter-Cable/Sterling 1000 ( the sander the 509 is based on), rebuild that, and send him on his way with an objectively better sander. Problem solved, right?

Thing is, the 509 was now sitting in the tool morgue in my garage, and the decrepit remains were praying on my mind for all the world like the Tell-Tale Heart. I mean, 509 sanders are pretty uncommon, as most of them, if used to any extent, died a similar death to our boy here ( minus the truly awful switch "repair"). Sometimes, when I have a tool or machine that's really just plain shot, I could almost swear I hear a quiet, Ringo Starr-like "help" every time I walk by it.

Recently, I was rooting through my finishing sander parts, looking for a better pad for a 145, when I looked at a box of 106 pad posts. These posts are longer than the ones used on the 509, and both the stud on the top and the threaded hole on the bottom are different sizes, but the thought occurred to me that I could pick four damaged ones, cut them to the appropriate height by removing the stud end, drill and tap the female end for the larger 509 hardware, replace the upper stud with a sheetmetal screw going through the bearing plate... for the limited use the sander would see in the shop, and with my usual vigilance about keeping my workers healthy, I felt it would work well enough to bring the 509 back into the land of the living.

What about the counterweight? the stub shaft and the offset blind hole on a 509 have a very shallow fit, and are only held in place by one tiny set screw ( this system didn't last too long, which is fortunate because it's horrible), and the 509 had a great deal of wear from slipping. Still, I could knurl the stub spindle, press it into the counterweight, drill out the set screw hole deeper, and voila, a repair of reasonable strength is made. I may go back and actually weld the two parts together if it doesn't hold. I don't have anything to lose.

With these repairs, and the bequeathing of an original, unused Sterling switch escutcheon, the 509 was revived, and with it, my collection of Porter-Cable finishing sanders was complete.

Oh wait, I don't own a 105. However, those were terrible sanders, so no great loss, I suppose.

In 1949, Porter-Cable purchased the Sterling Products Co. of Chicago, Ill. in order to add a line of finishing sanders to their line of abrasive machines. Having had a great deal of success with developing belt sanders, it may seem odd that they wouldn't design a sander in-house, but the sanders in question ( at least, two of the three) were so beyond reproach that they were the only match to the likes of the A-3 and BB-10.

There are three Sterling sanders: the pneumatic 1512,

Heavy, a bit clumsy to change paper on ( using the same type of spring-and-bar retainer found on many an automotive DA sander), but essentially indestructible. There is also the comically inadequate 105, a "buzz-box" sander that looks better than it works. Most importantly, we have the progenitor of all Porter-Cable/Rockwell finishing sanders, the legendary 1000.

The 1000 is a truly remarkable design. Running a gear set in an oil bath ( the transmission of a 1000 is sealed in a heavy rubber cover, and oil is added through the cutest lil' fill cap you ever saw) and featuring both air filtration for the motor and quick-change pads allowing sandpaper swaps in seconds, the 1000 was forged by the Old gods in the heart of a dying star. Provided that the oil is topped off and the hardware snugged up now and then, there's every likelihood that this sander will join Keith Richards and the lowly cockroach at the heat death of our solar system.

However, the 1000 was extremely expensive to make ( the kit, with air filters, oil, extra pads, and a case, retailed for 142.00 in 1951, or 1,522.00 and change in today's coin), and while it couldn't be beat for production finishing, a less expensive sander that would be purchased in greater numbers was an attractive idea to Porter-Cable.

Enter the 106.

Appearing in Guild catalogs by 1950, this sander was essentially a low budget machine that differed from the 1000 in the method of transmitting motion to the pad, the complex but adamantine oil-bath design being simplified into the four-posts-and-a-counterweight system that every successive sander would sport. This system has a few drawbacks, the largest being dust ingestion into the bearings and, in the case of the execrable three-piece counterweight found on the 509 and early 106's, prone to shaking itself to pieces. Nevertheless, the 106 worked well, sanded a little faster, and cost a lot less, being 49.95 in 1954 ( a mere 517.00 or so today). As is often the case with Guildtool designs, this sander was built for economy but was so well made for the price that it would be the second most popular of the finishing sanders, being made in some form into the Rockwell years. Less successful was the ill-starred 509, new for 1953. While the 509 has a great deal more 1000 DNA than the 106, the replaceable pad design of the 1000 was dropped, and the new sander used a captive spurred roller to hold the paper. The 509 did, however, retain the air filtration feature, albeit with a lower airflow, but much stouter front grille. I've always felt that the 509 looks a bit like a short man in a jousting helmet, what with the eye-level slot in the grille. This gallant fellow retailed for a cool 89.00 in 1954, or something like 920.00 dollars if bought today ( if only you could buy such a machine now...).

Over the years of production, the 106 had grown up a bit, having had the counterweight system redesigned into a much stouter affair, with twin sealed bearings and none of the stub-spindled,expansion-wedged tomfoolery of the earlier layout. Power was still transmitted via a round belt, made by Hoover in a factory less than five miles from where I grew up, though the later 106a would be retrofitted with a timing belt arrangement that was less prone to slippage with age and wear.

The next step in the evolution of the finishing sander was dust collection.

Joining the team in 1953, the 127 was, in essence, a 106 with a skirt and a fanny pack. The addition of a dust chute above the base frame that led to a rear-mounted bag was yet another stroke of genius from Art Emmons, and adding a pivoting dust skirt that could be lifted up out of the way for paper changes completed a very tidy bit of retrofitting. The 127 worked as well as its sister sander the 106, and production only ceased in the late '60s.

The Post-war boom in home handyman-type activities led to the development of a number of lower cost, lighter duty tools, and the finishing sander was no exception. Bonus points were given to tools that could pinch-hit in a number of rolls, and Porter-Cable had ideas about that, too.

Just in time for Christmas of '55, the 145 is the logical conclusion of building a low-budget finishing sander; in fact, the 145 is such an ephemeral design that it only has one ball bearing, the balance of moving parts running in bronze bushings. It's not a bad sander for all that- the 145 is so small that ( like the A-2 belt sander) it lends itself to the sanding of surfaces that are already assembled, making it handy for furniture refinishing. In addition, it's a good fit for people of small stature, and ideal for the grade school-aged shop boy or girl ( one can't help but wonder how many birdhouses, doll beds and pinecars the humble 145 has smoothed out over the decades). This design, while hardly suitable for industry, was popular enough to be offered until April of 1964.

Then there's the Routo-jig.

Marketed as a router, jigsaw, plane, and finish sander, it was mostly a router. While it wasn't all that great at routing ( except for laminate trimming, at which it triumphed), failed to inspire much confidence as a plane, and was downright useless as a jigsaw ( equipped with a sort of burr bit, it cut through sheet goods in any direction, hence jigsaw? How this is different from routing through sheet goods escapes me at the moment), it actually worked just dandy as a finishing sander since the sanding attachment was just the lower end of the tried-and-true 106. While the greater height is somewhat annoying, the amount of speed and power is comparable, and the 140 gives a credible performance for something that looks like it should be mixing cake batter.

It wouldn't be until 1963 that the ne plus ultra of finishing sanders was reached. By the end of that year, the two longest-produced finishing sanders of all time would blow everything else out of the water becoming the gold standard for finish work in cabinet shops all over the nation in the era before random orbit sanders and gel stains. I'm speaking, of course, of the iconic 330/505 sander platform.

The first point of departure was pad size. Instead of the conventional 1/3 sheet pattern, Rockwell offered a choice of the 1/4 sheet 330 or the 1/2 sheet 505. With a change in size came a change in fastening hardware; the roweled roller that had been used since 1949 was upgraded to the mousetrap style, a spring-loaded clamp that made changing paper faster and tool-free ( there was a key for the 330 to improve leverage. While I've seen them wired to the cords of many a 330, I've never known anyone who used it habitually). Both of these sanders were instant hits, the 505 being especially prized for the great speed with which it could prepare a cabinet side or drawer front for finish.

While the ROS is king these days, it does have one drawback; due to the greater movement of the pad ( which gives the ROS its speed at sanding), it's often necessary to sand a piece to a much finer finish to remove the sanding marks of previous grits. This tends to affect the ability of the material to take stain, since the wood fibers are, in effect, nearly burnished. I own a ROS, and American -made Porter-Cable 333, and while I do use it frequently, it's almost always for something that is to be painted; for all else, the 505 is the sander of choice. While I generally prefer the products made before the Rockwell years, the 505 was an inspired design that took the best of its ancestors and supercharged them, and I can honestly say that after having worked on a couple of hundred 505 sanders, I've never actually seen anyone ruin one, not even kids in shop class.

Production of the 505 was moved to Mexico ( my guess is that they were assembled, rather than fully manufactured, but that's speculation) after Black and Decker sunk their filthy claws into Porter-Cable's flank, but production of the last Porter-Cable finish sander ( the 1/4 sheet attempts currently marketed do not count. Not in this shop) ceased in 2009.

The vital statistics-

1000-8 lbs, 3/16" orbit, gear drive ( oil bath), 5,000RPM,1/3sheet

1512 ( Speed-Bloc)-8 lbs,5/8 stroke ( reciprocating), 3000SPM, 1/3 sheet

106-6lbs,1/4" orbit, belt drive, 4300RPM (idle), 1/3 sheet

509-8 lbs,3/16" orbit, gear drive, 6,000RPM, 1/3 sheet

127- 6 lbs, 10 oz, 1/4" orbit, belt drive, 4300RPM (idle), 1/3 sheet

145-5 lbs, 6 oz,3/16" orbit, gear drive,3500RPM (idle),1/3 sheet

140 (Routo-Jig) with 5026 sander attachment-6 lbs,1/4" orbit, belt drive,5,000RPM (idle),1/3 sheet

505-9 lbs,1/8" orbit, direct drive,10,000RPM ( idle), 1/2 sheet

330-3 3/4 lbs,5/64" orbit,direct drive, 12,000RPM (idle),1/4 sheet

While the cost of these sanders was a consideration in their ultimate demise, another factor is skill. For decades, people did their stock removal/heavy lifting with a belt sander and finishing with, well, finishing sanders. However, both of these tools require some experience to operate well ( the belt sander more than the finishing sander) and get the best results. The impulse of most users is to rush through finish sanding, but a slow, steady pace works much better, leaving less in terms of swirly little trails of scratches to obliterate with finer paper later. In the hands of an experienced user, any of these sanders can make a glassy smooth surface in a short time and still leave some pores in the wood to soak up the finish of your choice. I know several people who prize these sanders; I'm one of them, and I bet if you try one, you'll be too.

Long live the locomotive-the story of the Porter-Cable Take-About sander-Part five

The last stop on our tour concerns two sanders that, much like their ancestors the B-4 and B-5, were more or less the same machines save for scale. They were introduced the same year, and while one of them didn't survive the Pentair buyout, the other would keep the A-3/504 company to the end of the line. It's time to introduce the 503 and 500 Take-Abouts.

In early 1952, Porter-Cable introduced a pair of dustless belt sanders that summed up everything they had learned in the last twenty-five years.

February brought us the heroically proportioned 500 (Seen here in 'mid-'50s 500G2 Secret Agent Man government contract livery).

It’s the late ‘50s, and you’re on base serving your country in the war against roughsawn lumber. Your weapon? The porter-Cable 500G2.

The more svelte 503 joined the party in May.

The 503 as it appeared in 1952. A mainstay of Industrial Arts programs throughout the Midwest, I can’t begin to tell you how many 503’s I’ve rebuilt over the years.

The 500 is one impressive machine, combining many of the best traits of the BB-10 with the belt size and power of the T-4. The 500 was a slower sander than either, being 1440 fpm ( the BB-10 was 1475, the T-4 an absolutely ludicrous 1650 fpm); this was by design because the speed a belt is moving at must be juggled with the width of the belt/size of the platen to arrive at a compromise that removes material quickly without becoming uncontrollable, and the 500 is the most manageable 4"x27" sander in the family ( the B-4 only loses out due to the balance issue, but the lowset handles of that model go a long way to keeping it gritty side down on the work; the T-4 will do a very sincere Hemi under glass impression if you don't maintain a good grip on the front handle). Dust collection is very nearly as good as the BB-10, and the 500 is very stoutly built, with only the exhaust louvres ( Iknow, I know, it should be louvers. Porter-Cable called them louvres, take it up with them) being particularly delicate ( in all fairness, the T-4 had the same problem with both intake and exhaust grilles being easily smooshed). I really can't think of a downside to the design worth griping about, though the sander’s a little loud and the rear handle is a little small in diameter. I do appreciate that the toggle lever arrangement of the BB-10 was retained because I'm left-handed, and it makes for an ambidextrous sander. I suppose it would be nice if it were a bit quieter, but these are minor details- if you need a whole passel of something sanded down, you could do a lot worse than the 500.

The 503 is literally a 500 that got shrunk in the wash.

This level of compactness is due chiefly to the use of die castings; whereas the 500 is mainly sand cast ( you really can't build a reliable belt sander of that class any other way), the 503 owes a debt to the A-2 and A-3 sanders for the slim profile and light weight- it would be next to impossible to make the design the old fashioned way without it being far larger and a good deal heftier.

The 503 is the sander I have the most experience with, as it was far and away the most popular sander in this area for Industrial Arts classes, and teenagers are not known for being respectful of school equipment. It was very common for years to receive several boxes of these fellows before the beginning of the school year,in need of TLC to correct the various and sundry bent supports arms, stripped gears, and abraded cords (seriously, the cord goes over your shoulder, guys. Keep it off the table, for crying out loud). Not that the sander was a lightweight- few people that used them with any kind of sense ever wore them out. It's just that, if you locked a teenage boy in an airtight rubber room with a wooden mallet and two stainless steel ball bearings, in one hour he would have broken one and lost the other.

The ivied halls of academe can be a dangerous place.

The 503 is an excellent sander, fast, light, and capable of hard work. However, the light castings don't lend themselves to a knock-around life on job sites, and it's not uncommon to see this sander in a shop-built, wooden case for protection. It's like I always say, a tool case is cheap insurance, and while Porter-Cable offered a case for the A-2, the other sanders were left to their own devices.

The 500 made it as late as 1977, and while I've never seen a Pentair era, Porter-Cable badged example, it may very well have survived a few more years. The 503 fared better, being offered with the 504 until Black and Decker decided to become anti-worm drive extremists and pull the plug on the locomotive sander once and for all between 2009-2011. Parts were available for several years afterward, and I could kick myself for not buying more worm gears when I had the chance- the 30 of them I did get didn't stretch very far.

Finis:

500:4"x27" belt,1440 fpm,25lbs

503:3"X24"belt,1100 sfpm,15lbs

Today, these sanders command prices that may sometimes rival the original MSRP. I scout local flea markets for them, check used tool dealers and craigslist, but some of my favorites were scouted out by friends. I dug my treasured T-33 out of an aluminum scrap bucket,. My cherished B-10 was intercepted by a friend on its way to the scrapyard. My prized A-3 was given to me by a customer who was too old to use it anymore. Every one of them is a valued tool, an admired objet d'art, and an irreplaceable part of the story of a company that changed the way work was done.

If you should run across one of these sanders, I encourage you to bring it home. Blow the dust out. PUT OIL IN IT. Then find a piece of lumber that looks like the bottom of a shoe, or a table that really needs refinishing, or even a workbench that has a warped top and one too many nails in it for a plane to contend with, and watch the magic happen. You'll be glad you did, I think.

Just don't be surprised if you wind up with your own roundhouse someday.

C’mon, everyone get in the shot!

After all, what's more important than family?

Long live the locomotive-the story of the Porter-Cable Take-About sander-Part four

I'd like to shine the spotlight on a sander that shouldn't have to share the stage equally with another model in this little history because it has no equal. The Take-About in question wasn't the biggest, or fastest, or longest made, but it was the most well-rounded design in all the years Porter-Cable offered worm drive sanders; great for stock removal, but controllable enough for finer work, with superb dust collection, excellent balance and surprisingly little noise, and virtually indestructible in the hands of any higher primate.

I give you the BB-10, or, as Porter-Cable called it, the Tool of Tomorrow.

The BB-10 was the best belt sander ever built. Fight me.

First encountered in 1942, the BB-10 was the result of lessons learned from the B-10, of which it is the only close descendant. The BB-10 kept to the basic layout of a 1hp, 3"x27" sander with dust collection, but the issues with heat that plagued the B-10 were firmly dealt with in the new design. The BB-10 has both a fan for keeping the motor cool and an impeller for moving the dust which allows each part to do its job well, instead of one compromised component struggling to do either task. Because of the care taken in construction ( the motor fan is an axial squirrel cage affair and the dust impeller is a cast aluminum, balanced job), the BB-10 has better dust collection than any of its littermates, and rarely breaks a sweat under even the heaviest tasks. The intermediate gear was also replaced by two sprockets and a leaf chain fully 3/4" wide, which helped lower the amount of noise.

Ain’t it a beaut?

The new sander in town also did away with what I refer to as the goblin shark profile of the B-10, opting for the distinctive concave face that gives it much of the look of a streamlined locomotive engine, complete with cow catcher. This isn't just for looks- not only does it beef up the front of the sander frame to better withstand the rough and tumble life of a belt sander, it also lends itself to a modified grip for using the sander on the vertical plane; simply hold the front knob in the web of your hand between thumb and index finger, keeping the heel of your hand away from the idler pulley, and the BB-10 can be held against a wall or other vertical surface comfortably.

Speaking of using the sander at an odd angle, the BB-10 could use the B-10 bench stand, which converted it into a species of edge sander.

I have the good fortune to not only have one of these accessories but to own a BB-10 with a special order rubber-coated front roller to use on it; this allows the user to sand inside curves smoothly, which doesn't always work well with the bare aluminum pulley found on most examples.

The BB-10 had four known running changes during its nine-year run, most of which were cosmetic- the forked switch lever became a capped one that could be removed without dismantling the switch cover, the front knob stud went from having a hexagonal post to a round one, then back again, and the wooden handle was discontinued by 1944 or so, being replaced by the bakelite loop shared with the later 500 ( the A-2 would keep its unique smaller wooden handle until 1958, but the larger maple grip would only be found on the BK-12 saw and RC deck crawler after '44- it would never reappear on another Take-About). Where it counts, the BB-10 never changed, and never had reason to, being an irreproachable machine and a home run from the word go.

The BB-10 retailed for 148.00 in 1945, or about 2,200 dollars. It was worth every penny to the person with a lot of sanding to do, and while I reserve specific tasks for each of my Take-Abouts I will admit that I reach for one of my BB-10's (Yes, I own four of them. No, they're not for sale) for the majority of sanding jobs.

Vital statistics-

BB-10: 3"x27" belt, 1475 fpm,23 lbs, , 1 hp motor

By 1950, the success of the 503 ( which we'll discuss next time) prompted Porter-Cable to develop a larger version, the 500, and for one short year, the two juggernauts stood cheek to jowl in the catalogs. The newer sander would ultimately win out and go on to be offered until the Pentair years, but the curtain fell on an absolute masterpiece by the end of 1951.

Long live the locomotive- the story of the Porter-Cable Take-About-Part three

We've discussed the G-3, the Guildtool belt sander that escaped obscurity by leading to the development of the modern worm drive belt sander. Now it's time to turn our attention to the Guild sander that no one liked but people, and the descendant of the G-3 that still defines the belt sander to generations of woodworkers to this day. I refer to the 2-A/A-2 and A-3/504 sanders.

I've mentioned that the Guildtool line was directed at the home hobbyist as an affordable line of power tools at a time when there really wasn't such a thing ( other than the drills that everyone and their maiden aunt cranked out-those were legion). A belt sander is hard to cheapen up without sacrificing quality ( not that this has ever stopped anyone, Black and Decker), and while the G-3 tried to reduce costly hand finishing by being rectilinear, the 2-A approached the issue from a more cutting edge (in 1936) standpoint.

The original 1936 Guildtool 2-A, loved by everyone but the W.P.B.

This little fellow ( 2"x21" belt) is chiefly made from die castings, which had been pioneered in everything from appliances to ashtrays but was largely uncharted territory for a power tool at the time. What few tools that used this technology were lackluster at best, but the 2-A was quite a different story.

Die castings made the sander lighter (9lbs) and more compact, but the greatest advantage accrued was the dramatic reduction in labor required to turn a raw casting into a finished piece. The 2-A was still hand fit (that would be the case with most Porter-Cable tools until the development of the 346/315/368 platform of saws in the early '60s), but the castings came out of the machine with a much finer surface, which took less time to polish up.

Additionally, the 2-A ( or, as it soon became known, the A-2) forewent the separate worm of the earlier sanders , having it cut into the end of the armature shaft. This feature (I'm using the term loosely) would not be repeated in other sanders, but it saved labor, machine time, and space, all of which made the petite A-2 thirty dollars cheaper than the T-33 by 1947 ( that's about 350.00 in today's money). Being such a felicitous combination of inexpensive, well constructed and of handy size for smaller projects, the A-2 was hugely popular, so popular that Porter-Cable had to have two motor manufacturers producing fields and armatures to meet demand (should you disassemble an A-2, a brown armature and field were made by Dumore; a motor with blue laminations was from Robbins and Myers. Don't mix and match, they aren't compatible). In fact, the only hiccup in the entire twenty-two-year production run was the period in 1944 when manufacturing of the A-2 was halted by order of the W.P.B. for the duration of WW2.

By 1953, the A-2 was incorporated into the main line of products, where it would stay until 1958 when the first belt-driven sanders were introduced. Unable to compete, the A-2 was discontinued. While the belt drives were cheaper and used wider belts, they had poor balance and were less robust as our little fellow, whose only true drawback was the need for the worm drive oil to be kept topped off. The concept of a compact worm drive sander would be revisited during the 2000s in the form of the 371, but let's face it, those kinda sucked.

Meanwhile, a new sander would see light during the war that married the technological advances of the A-2 with the innate durability of the T-33, and did it so well that it would outlive all the other Take-Abouts, including the ones that came after it.

Say hello to the iconic A-3.

The A-3, c. 1948. The gold standard of belt sanders for the next 67 years or so.

Appearing in 1944, the A-3 is, in essence, a T-33 sander stripped down to its fighting weight. The A-3 was die-cast throughout, which gave it the weight and labor savings of the A-2, but it retained the T-33 performance envelope and even shared a gear set with its predecessor (at first). The A-3 wasn't a winner right out of the gate, though. The earliest version was somewhat lacking in ventilation, requiring lower air slots to be milled into the front endshield.

There is also the small matter of the expansion plug fitted into the frame to access the gearbox. This system works well enough if snugged up judiciously, but is easily deformed by being cranked down, and many early A-3 sanders bear a layer of silicone or JB weld slathered over this plug like margarine on a cornbread biscuit.

The A-3 was quite popular. There was even a version made with an air motor ( for the factory where air lines were more frequently encountered than 115 volt receptacles), the 61-E, made for them by Rockwell's Buckeye Tools division in Dayton, Ohio,

The equivalent of your vegan aunt, the 61-E eschewed the usual diet of electrons.

While several minor details changed throughout its production run, the basic blueprint was sound enough that it survived through the Rockwell years ( renumbered as the 504) and the Pentair period, only to be felled five years later like a mighty oak by the bloodstained, money-grubbing hands of those unmitigated bounders who make everything out of yellow plastic. Production would cease after sixty-seven years, making it the longest-produced handheld power tool of all time.

There are better sanders than the A-3. If I'm honest, it doesn't even make my top five. A-3's are easily damaged if they get dropped. They were built so lightly that later versions had additional wear plates scabbed on to counteract the effects of a poorly tracking belt. They're prone to loose brush holders, oil leaks, and derangement of the idler pulley support arm if dropped. Think of a T-33, take away the impressive airflow and ruggedness, and you have an A-3.

That being said, I've easily repaired a hundred of them in the last twenty years, they're fast and light, and I've seen them survive abuse that would promptly murder a modern belt-driven sander.

Then, of course, there's my personal experience with the breed.

My A-3 was bequeathed to me by an old customer who has long been in his grave. He purchased it in '48 when he got out of the Army. He used it and a K-75 circular saw to build homes for decades, and when his oldest went to work with him in the '60s, the son went and bought his own, which saw just as much use. They even went so far as to buy a third in the late '80s. I repaired a number of tools for this man over the years, and when he brought the sander in for service and we talked about what a great sander it was, how much he used it and how it put food on the table for his entire working life, he slid it across the bench to me and said that he wanted me to have it. I'm a fairly stoic fellow in general but damned if I wasn't misty-eyed. I rebuilt it, of course, and while it isn't my go-to sander, I still take it off the shelf for the odd sanding job. I'll never part with it on this side of the river, and I hope someday I can pass on Mr. Sherman's act of kindness to a fourth generation of admirers.

So yeah, I like the A-3 well enough.

The team:

2-A/A-2: 2"X21" belt, 600 fpm,,9 lbs, Dumore or Robbins and Myers motor

A-3/504:3"X24"belt,1600 fpm14 lbs,3/4hp motor

Nothing succeeds like success, and these two sanders were very, very successful. But they stood in the shadow of their contemporary (literally, it was quite a bit bigger), which I maintain is the all-around best worm drive belt sander ever made, the big, beautiful BB-10.

Long live the locomotive-the story of the Porter-Cable Take-About sander-Part two

The next part of our story is a bit complex. You see, by the mid-'30s, Walter Ridings' instincts for the burgeoning power tool market had been proven correct, and he now turned his attention to the home market.

Enter the Guild line.

Before WW2, power tools were the province of heavy industry ( Milwaukee had been saved from bankruptcy after a factory fire chiefly by a large order for drills from Henry Ford), and even home builders rarely had more than a RAS or a circular saw ( I mean, a singular circular saw; it was not uncommon for one worker to cut the lumber and everyone else to busy themselves nailing them up). Handheld power tools were almost unheard of in the home shop. This isn't surprising when you consider that a B-5 would set you back 78.00 in 1936, or roughly 1,400.00 in today's coin- you would have to be awfully busy in the garage or basement to justify spending that kind of scratch.

Ridings, however, saw a future in providing a small but comprehensive line of low cost, high quality power tools to the avid home shop man ( and the contractor that could squeeze a nickel until the buffalo had bruises). For reasons that doubtless made sense at the time, this line of tools was kept far apart from the commercial Speedmatic and Take-About line. The company was known as Syracuse Guildtool, and it was located at 1720 N. Salina Street. The Porter-Cable Machine Company building was located between 1710 and 1720 N. Salina, so it's fairly obvious that GuildTool was not that far away from the apron strings. There were only ten tools known to be sold under this name: the A-4, A-6, and A-8 circular saws, 1000 router, 106 finish sander, 103 hedge trimmer, HT hedge trimmer, E-6 rotary flooring edger, and two belt sanders. The more often encountered model, The A-2, will be discussed a bit later; the one we're interested in at the moment was known as the G-3.

I have mentioned that the products offered by Porter-Cable were taken from raw castings to mirror-polished tools almost entirely by hand, and close examination of a given tool made before the mid-'50s will often reveal numbers written in red grease pencil to keep the castings together throughout construction, as the individual parts were actually faired into each other, making them hard to interchange. This level of fit and finish makes for a superb machine, but it isn't cheap, and the two belt sanders sold under the Guildtool aegis approached the issue of economizing hand-finishing from different angles. The A-2 ( or, as it was originally known, the 2-A) made use of die castings, a fairly recent development at the time but one that allowed a casting to be made with an accurate, smooth enough surface that sanding and grinding weren't necessary, leaving only minor snag grinding and a trip to the buffer before assembly.

The G-3 reduced finishing by being shaped like a brick.

The complex, organic shapes of the B-series sanders were eschewed for a slab-sided, trapezoidal body. This rapidly sped up the process of sanding the surfaces smooth because the parts could be locked into a jig and crammed into the waiting maw of a belt grinder ( if you peruse a Porter-Cable abrasive finishing machine catalog of the '40s, you will see a number of familiar castings- the G-8 belt grinder was even available with a lever-feed table to increase the production of small parts). As a result, the G-3 and its descendants are immediately recognizable for their angular frames.

The G-3 shared a drivetrain design with the B-10, using an intermediate gear to power the drive pulley ( the A-2 used a silent, or leaf chain, a design that would prove popular. This, I think, was largely due to the space constraints of such a tiny belt sander). Unlike the sophisticated system found on the B-10, where a helical gear ran on twin magneto bearings, the G-3 used a straight cut gear running on a bronze bushing, making the G-3 a simpler, if louder, sander.

Unfortunately, the G-3 proved to be unpopular with the average home handyman, as it was hardly as cheap to make as an A-2, and at some point in 1935, the G-3 was added to the commercial line and rechristened as the T-3.

The T-3. Not the most successful of designs, but one that taught Porter-Cable a number of lessons.

The T-3 was offered alongside the B-5 for only one year before the matriarch of the family was dropped from production and within a few years the T-3 was upgraded to a chain drive, making it somewhat quieter and a bit more reliable. However, Porter-Cable kept their finger on the pulse of the tool market, and it was soon discovered that the 1/2 hp T-3, while adequate, was somewhat lacking in performance, and the sander tended to run a bit on the hot side when used for long periods, as the ventilation was inadequate. The decision was made to develop more powerful sanders along the same lines. While one of them hit the mark so well that it laid the groundwork for worm drive sanders into the 2000s, the other was such an overpowered titan that it barely made it five years before being discontinued.

The T-33 in stock form was a thing of Art-Deco beauty.

New for 1939, the T-33 was more or less right from the beginning. Merely one inch longer and a pound heavier than the T-3, it was fully a 1/4hp mightier, and while the belt size and speed didn't change ( 3"x24", 1350 fpm), the added grunt makes the T-33 better suited for heavy work, while the mass and shape make it an easy belt sander to master- I call my T-33 the world's fastest finish sander because you can do surprisingly fine work with it with some practice.

The airflow was improved on the T-33 by the addition of what amounts to a hood scoop. Unlike the T-3, which has a solid front endshield, the T-33 has an endshield that is more or less just a cast bearing hanger, with massive openings around the armature's end. This, combined with a stamped cover that gives the sander something of an art deco look.

The air intake of the T-33 was massive. No overheating for this guy!

This gives the T-33 airflow that a Dodge Superbee would be proud of. The earlier, thumbscrew adjustment for tensioning the belt was replaced by the lever type action that all later Take-Abouts would rely on. As a result, this handsome fellow ( I mean, look at those fluted edges!) was well suited for heavy use and is by far the most commonly found Take-About sander of its time. The stout build and commendable performance made it a hit with everybody, from contractors to Industry to the Armed Forces, and while all Take-Abouts could be had in any voltages required, the T-33 is most frequently found in other voltages ( all made by General Electric), from 110 and 220 single-phase models to a three-phase motor designed and built for the Army Air Corps (shown on the right in the photo below).

220 volt, 11 volt, or three phase, the T-33 could solve the user’s sanding problems.

This Goverment contract oddity incidentally makes the T-33 the earliest known example of a brushless power tool.

While the T-33 was a hit, the last of our T-series family was a solution that never found its problem. What can we say about the T-4?

You didn’t buy the T-4 because you loved sanding, you purchased it because you hated wood.

Appearing in catalogs by 1937, the T-4 is 29 pounds of overkill. Powered by a motor making a whopping 1-1/4hp, the 4"x27" belt makes using this big chungus for any length of time a feat of strength, and anything less than 80 grit will cause the T-4 to behave like an excitable rottweiler, pulling on your arms for all its worth and requiring both hands to keep at heel; in fact, a T-4 will do a drag strip worthy wheelie if the front handle is released ( there's a reason the T-4 doesn't have a front knob, no one short of Popeye has that kind of grip). I've found my T-4 indispensable for handling rough sawn and reclaimed lumber, as no amount of dirt, bark or buried hardware even fazes the big lug. The simple lines of the earlier T-series sanders have been bulked up until this powerhouse resembles a scale model of a brutalist apartment building. The T-4 is gargantuan, strong as an ox, and ( how should I put this) as short on looks as it is long on moxie.

The T-4 was originally offered with an integral aluminum grip, just like the first B-5's, but this was swiftly changed to the tried-and-true maple handle. Another peculiarity of this sander was that it could be purchased with or without dust collection; this was also true of the B-10, but while the B-10 was only given a different fan and the dust nozzle was blocked off, the T-4 had an entirely different rear endshield.

An additional idiosyncrasy of the T-4 is the tendency of the aluminum frame castings to discolor; I've repolished my original T-4 at least three times, only for the finish to dull in a matter of months. I don't really mind, though.

Ever see a belt sander with a skin condition?

I feel that the T-4 may relish in its brutish appearance. As a boy, the Thing from the Fantastic Four was my favorite superhero, and I can just picture this equally hulking New Yorker looking at an unsuspecting board and bellowing, "it's clobbering time!".

The cast:

T-3:3"X24"belt, 1350 fpm,15lbs, 1/2hp GE motor

T-33:3"X24"belt, 1350 fpm, 16 lbs, 3/4hp GE motor

T-4:4"X27" belt, 1650 fpm, 29lbs, 1-1/4hpGE motor

While the T-3 and T-4 would take their last bow by Jan 21st of 1942, the T-33 would soldier on (literally, in many cases) until 1944, when it would pass the torch to the longest-produced power tool of all time, the immortal A-3.

But that's a story for another day.

Long live the locomotive- the story of the Porter-Cable Take-About sander- Part one

Some time back, I was discussing Porter-Cable belt sanders with an acquaintance when it dawned on me that, unlike the history I reviewed at length in my thread about owning way too many circular saws (no, I don't really think that), I've never really put the belt sanders in anything resembling chronological order. This is an oversight on my part; after all, the belt sander was every bit as much a part of the company's bedrock as the saws. Moreover, the handheld belt sander was invented by Porter-Cable's own Art Emmons, who reimagined the circular saw and came up with an entirely new type of tool before he was thirty years old. His ingenious solution to one of the most laborious shop chores would span eighty-three years and would become the standard by which all later derivatives would be measured, and far and away, found lacking. This mighty bloodline would go from strength to strength for the better part of a century, to only meet their demise at the hands of a company that never mastered the concept. I speak of the Take-About sander, in its manifold forms.

Let's meet the family, shall we?

left to right: 500, 503, T-4, T-33, T-3, BB-10, B-10, B-4, B-5, A-3, A-2

Our story starts in 1906. Porter-Cable was begun as a jobbing concern, wherein a customer could have an item manufactured if they didn't have the means to make it themselves. Originally, this was often automotive in origin- Hannah acetylene starters, jacks, steering wheels, and even a parking brake for Ford cars designed by inventor/businessman/dieting guru George G. Porter himself. By the 'teens, they had struck out on their own as a manufacturer of in-house designs and were making a number of tools for the machinist, including vertical heads that could be retrofitted to older horizontal milling machines, a lathe designed for high volume operations and even a line of endmills and a boring head. by 1916, the firm was sold to Walter Ridings, a visionary who had cut his teeth working for Syracuse Supply and acting as president of the Manufacturing Association of Syracuse. He established himself at the helm of the firm as president, and though the Porter brothers and Mr. Cable were savvy businessmen in their own right, most of the advances the company would make until the end of WW2 were the result of Ridings' acumen. For starters, he purchased the site on Salina Street that would be Porter-Cable's home for decades; he purchased Mulliner Enlund for their lathes, Syracuse Sander for their sanders and band saw, and, most importantly, hired Art Emmons.

Walter Ridings had taken notice of the growing demand for handheld power tools, and couldn't help but notice the success Skil was having with their worm drive saw. He foresaw Porter-Cable taking the lead in this fledgling field of manufacturing, and he couldn't have picked a better engineer to bring his conception to life than the young man who was tasked with developing strategies for easing the burden of the worker. Focus was directed towards two of the most onerous tasks- sawing and sanding. Emmons hit the ground running by developing a saw that was so well balanced it could be operated with one hand, then batted one out of the park with the first portable belt sander( or, in company parlance, a Take-About) ever, the brilliant B-5.

The original article, kinda; this “Mark 2” B-5 was made around 1928.

Compact, robust and just plain handsome, the B-5 was a remarkable design, using the technology of the time to great effect. Tools of this period were made from sand castings, and as a result required a great deal of handwork to finish the parts to a high polish, making them, in effect, nearly hand crafted creations the equal of a quality firearm. By mounting the motor vertically, Emmons powered the drive pulley without any chains, sprockets or intermediate gears- the drivetrain is a worm drive system in its purest form. The only true downside of the design was the inherent poor balance due to the offset motor, which was countered by a rear roller and made up for by an extremely low operating grip, making it handle quite a bit like a hand plane; mastering a B-5 is child's play, and it is pleasant sander to use if a little sketchy on edge sanding. Original models had a rear handle that was aluminum and an integral part of the frame casting, but issues with users being shocked led to the replacement of this feature with the maple handle that would go on to be used on half of the B-5's successors ( and even a saw or two). The B-5 is found in three main versions, the original aluminum handled version, the more commonly seen wooden handled style with the polished finish, and the later painted surface. My version is what may be regarded as a "type 2", and incorporates a heavier casting around the front handle mount and wear bar area. Oddly, my B-5 bears an early tag, but was made about two years or so after the original design, possibly due to the factory finding some old tags laying around.

Art Emmons was twenty-six years old when he invented the B-5. Let that sink in a second.

The B-5 was followed closely by the larger B-4,

Give a B-5 the Charles Atlas Dynamic tension method handbook, and you have a B-4.

a 4"x27" sander that was essentially a B-5 on steroids. This sander benefited from the wider belt, being less prone to rocking, though the rear roller was kept. While both sanders were designed to be regreased without being dismantled, the B-4 used a grease cup from the circular saws to grease the idler pulley- just remove the belt, remove the slotted screw in the face of the pulley, thread in the grease cup and refill the bearings. This should give some idea of the level of work these sanders were intended to handle, and it's no surprise that the average B-5 or B-4 is still functional if any attempt was made to keep the oil topped off.

Both sanders were very popular ( the B-5 being helped by having a captive audience- early B-5's have no model number on the tag because there wasn't another model of belt sender on earth at the time), and survivors invariably have a lot of mileage on them. There were two other variants, the B-44 being a B-4 with a small idler pulley, allowing it to sand floors up to the shoe molding ( a concept that Black and Decker tried, and failed, to repopularize decades later), and the even more ephemeral G-44, a version of the B-4 referred to as a sander-grinder. I have seen a picture of the G-44, and cannot determine what the difference is; confusingly, the other photo in the catalog of the G-44 is clearly an early B-5. I've yet to see an example of either sander in the wild, and I probably never will.

The other sander of the period was the B-10.

The B-10. Turns out that longitudinally placed motors are where it’s at.

Appearing in 1932, the B-10 complete departure from the original platform. The B-10 incorporated dust collection, which was the deciding factor in the design. The motor was mounted horizontally on the long axis of the frame, necessitating the worm drive being redesigned to use an intermediate gear to run the drive pulley. This gear is a work of art, being a helical cut affair rotating on a stud via twin miniature magneto bearings, and the drive system is very stout. Additionally, the B-10 used an idler pulley that had a rubber coating just like the drive pulley, making it excel at sanding inside curves and improving performance when used as an edge sander with the optional stand. However, the B-10 suffered from one serious fault. The system used one impeller to collect dust and pull air through the motor housing, an idea that Rockwell would resurrect in the 337 sander of the late '60s. On a belt-driven sander, with the fan/impeller close to the armature, the system works fine. On a worm drive sander, this isn't possible due to the dust collection being mounted at the rear of the machine, and the B-10 fan is a good 4" away from the motor, on the wrong side of the gearbox. Airflow is through twin crescent-shaped openings in the casting (the B-10 is a marvel of the patternmaker's/foundryman's art if nothing else), and the B-10 simply can't breathe as well as it should. Don't get me wrong, I love my B-10 like a child, and often find myself gazing lovingly at its goblin shark profile, but a flaw is a flaw.

The B-10 was made for eleven years, but surviving examples are hard to come by due ( in my opinion) to the chronic overheating of the design when used as hard as the earlier sanders. The early B--10 used a pair of adjustable casters at the rear, much like a floor edging sander, but later versions deleted this feature. Balance of the B-10 is excellent, and it can sand with the best of them. Just let it cool down once in a while, okay?

Our players:

B-5: 3"x24" belt, 1250fpm,14lbs, 1/2hp GE motor

B-4:4"x27" belt, 1650 fpm,23lbs, 1hp GE motor

B-10:3"x27" belt, 1475 fpm,21lbs, 1hp GE motor

These three sanders were very innovative, and Emmons had explored the concept to such extent that the later Skil A and B sanders actually made use of one of his patents for a gear train. Skil would become the only real competition in the world of worm drive belt sanders Porter-Cable would ever have, but Porter-Cable did it first and, if you ask me, did it best.

Join us next time, when we discuss the short-lived but influential T-series sanders.

I own sixty-eight circular saws, and that’s utter lunacy, part seven- A worm drive/ Rockwell double feature

Welcome back, everyone. Today's discussion is a double feature: we'll be covering a peculiar family and one of the few times Porter-Cable followed someone else's lead, the worm drive saws, and wrapping up the family tree with the last of the Mohicans, so to speak.

Porter-Cable started out as a jobbing company. In other words, you could ( if you were alive 114 years ago) go to the firm with a set of drawings under your arm, walk up to the sight of George Porter pigging out on a baby carrot, and have a widget made to order. The company made any number of non-tool related items, from pencil sharpeners to automotive steering wheels, but they were mainly manufacturing metal lathes and milling machine attachments ( and forging the occasional vise) until the hiring of Arthur Emmons, a young fellow who would prove to be the most prolific power tool inventor of all time. As I have previously mentioned, this bright young fellow would invent the portable belt sander and the first helical geared circular saw, the K-9 ( the K-8 was of similar appearance but had no gearing at all, being directly driven). Porter-Cable president Walter Ridings knew a good thing when he saw it, and the company made some genuinely great sidewinder saws, as we have seen. The day would come, however, when Porter-Cable would try their hand at making a line of worm drive saws. Not small trim saws, like the well-regarded A-4; these machines would be intended to compete ( East of the Mississippi, at least )with the Skill 77, the original hand-held circular saw design. I'm speaking of the 533, 567, and 568.

Left to right: 568, c. 1963 , 533, c. 1960

In 1959, Porter-Cable introduced the 533. A worm-driven, pivoting foot left-hand circular saw, it owed much of its design to the extremely popular Skil saws of the past thirty-seven years ( I'm not sure who was responsible for drawing up the plans, but they definitely looked over Skil's shoulder, a far cry from the times when Skil had to pay royalties to the NY boys in order to make the A and B belt sanders). The blueprint was followed so closely that some Skil saw parts, such as adjustment knobs and even the base, can be persuaded to fit the Porter-Cable. The Porter-Cable differs only slightly, being made with off-the-shelf bearings and seals, making rebuilding less of a task. The 533 is a bit stouter in some aspects, but the two saws are neck and neck in terms of performance.

By 1961, the 533 had been supplanted by the 568, which differs in being slightly slower and a half pound lighter and being one of the first saws to adopt the beautiful, exciting putty gray and satin black painted finish Rockwell would slather on any number of tools in following years to avoid firing up the buffer. The family would be rounded out with the addition of the 567 in 1964. This saw used a 6 3/4" blade and was a bit lighter still, but the three saws are very closely related, diverging only in scale and finish.

On the whole, the three saws are excellent machines, very rugged and plenty powerful, but they didn't do anything that the contemporary Skil saws couldn't do better, and even though the 567 and 568 were on the books up to the Pentair buyout of 1981, they just weren't that popular. They remain a curious decision on the part of a company that had no business deviating from the role of trailblazer.

It's time to conclude our brief history of Porter-Cable/Rockwell circular saws. There are a number of places we could end the story; when Rockwell purchased the company in 1960 or when the last saw to feature a grease cup ( the 315-1 and its ilk) debuted in the late '70s. For my part, I'll stop in the middle, with the last aluminum-bodied saw to be introduced and the standard bearer for future generations of users. Let's look at the remarkable 315, or (as I think of some of the examples that have come through the shop) the saw of Theseus.

Appearing in the April catalog for 1964, the 315 was the bare bones version of the well appointed 597, which was itself the logical evolution of the highly successful 115 platform. The castings are tumbled rather than polished, lending them an "orange peel" finish, and the fit and finish is not as precise ( the castings are designed to allow for some misalignment, making the 315 an easy saw to Frankenstein back together from multiple donor saws). Accuracy and power are still respectable, and the wraparound base, inherited from the 115a provides plenty of support, although it precludes cutting up to a vertical obstruction, such as making a pocket cut for a floor grate near a wall. The 315 has two sister saws, the 346 that debuted at the same time, and the larger 368, welcomed into the fold later that same year.

The 315 and company have a few minor faults. The two wrench system of the 115 has been retained ( somehow, people always lost the jackshaft wrench- they are now lost to the ages like all the Unisaw dust doors), which is a bit awkward, and several saws left the factory with a base that does not properly align with the cut, making it difficult to saw to a line without a guide; I've seen too many examples with this problem for it to be anything but a manufacturing fault. The only other real issue is the tendency of the handle to bow under the repeated stress of being used to push the saw, resulting in a noticeable gap between the outer handle half and the handle base. This is due to the lighter castings and is an issue shared with all of the saws in this family ( the 315,346,368, 596 and 597).

As I said earlier, the 315 had a sort of harbinger in the form of the 596,

and the larger 597, which first arrived on the scene in early 1963. These saws are the deluxe version of the same concept. These two saws differ in having more powerful motors, a mechanical brake that worked against the fan ( a larger, cast aluminum affair with a pronounced outer rim) , and a sort of micrometer adjustment for depth. The 315 would share the same basic castings ( although the handle is different, not having provision for mounting the brake button and linkage) , and the later 368 would use the same armature as the 597, but if the 315 is a base model work truck, the 597 is the version with powered windows and heated seats- it's a very luxurious saw, at least in comparison to the more spartan 315.

There are variations of the 315, but they're limited mainly to cosmetics ( and the fifteen-minute window when the saw was known as the 215, for reasons only Rockwell understood). The basic design was by far the most popular saw Rockwell would ever make, being constructed for thirteen years, and the 315 survived in enormous numbers due both to being a durable design and being easily repaired; there are saws brought into our shop for repair that have had every single part other than basic hardware replaced over the decades, a testament to how well-liked the design is. For my part, the 315 is the P.C/Rockwell tool I have the most experience with- I've probably repaired or rebuilt seventy or eighty of them in my time, and my boss, Dave, has likely worked on hundreds of them. To this day, I still regularly see them, almost always in the hands of someone 40 or under who inherited them from their father or grandfather. It is a comforting thought that the remarkable bloodline of innovative, robust, hardworking saws that stretches back to the brainchild of a twenty-five-year-old named Art Emmons still commands some respect, even now.

The 315 is often considered to be one of the best circular saws ever made, and are so sought after that I've had every 315 I've repaired for myself begged from me over the years- it wasn't until fellow OWWM'er Mike Levine sent me this example that I stopped allowing myself to be talked out of them! Personally, I would argue that there are far better machines in the family, with more power, greater accuracy, and better looks. That said, nothing succeeds like success, and the 315 was a highly successful design.

Later designs would be developed to make a double insulated version, known as the 315-1, a good saw in its own right but as dull as a beige living room. The artistry of the power tool ( for me, at least) did not survive the transition to plastic, making the 315 the last of a very distinguished family.

Our saws:

533: 4,500 rpm, 7 1/2" blade, 17 1/2 lbs

567: 4,800 rpm, 6 3/4" blade, 14 lbs

568: 4,200 rpm, 7 1/2" blade, 17 lbs

596: 5,800 rpm, 6 3/4" blade, 14 lbs

597: 5,800 rpm, 7 1/4" blade, 14 1/2 lbs

346: 5,800 rpm, 6 3/4" blade, 12 lbs

315: 5,800 rpm, 7 1/4" blade, 12 1/2 lbs

368: 5,250 rpm, 8 1/4" blade, 13 1/2 lbs

Epilogue- when I started this thread, I thought I was being a bit obsessive about collecting Porter-Cable power tools. Today, I know I am. I've had a great deal of enjoyment in doing so, from the thrill of the hunt and the challenge of resurrecting some truly rough examples, to the gratitude for the efforts of fellow OWWM members in helping find so many of the missing puzzle pieces ( many of my most prized workers were not the result of my vigilance; rather, a number of them were handed to me, almost on a platter).

I currently am the owner/caretaker/foreman of 57 circular saws. Some of them were purchased by home handymen and barely used; others bought by contractors or industrial concerns and used to hell and back. A few of them served their countries, like my USAF K-89. All of them are highly prized, carefully used, and lovingly maintained. I will probably never have an example of every saw, and I've come to terms with that ( but I'll still going to try).

There are 12 known saws that I have yet to find:

K-8

K-9

K-12

K-65

Kwik saw

168a

76

177

567

592

597

597a

Some are hen's teeth, and some are inevitable finds. A few are legendary, and some are notorious. All are fascinating components in a very long story of one company's influence on how work has been done for decades. I'm hoping I've given some explanation of why I find them so interesting, and perhaps you'll find them interesting, too.

I own sixty-eight circular saws, and that’s utter lunacy, part six- The Standard duties

I had mentioned previously that by the 1950's, Porter-Cable had divided their circular saws into three levels of build quality: Standard duty, Heavy duty, and Super duty. This distinction was a sensible one, as the very best of the saws were enormously expensive and designed for extremely hard work, and buying one for home use would be the equivalent of owning a full-sized, four wheel drive diesel pickup truck for commuting to your office job- and who does that?

The Standard/Heavy/Super duty designations were the logical extension of the "ABC" system of dealer levels adopted in the very early '50s: "A" dealers were purveyors of the highest quality equipment only, selling to industry, the "B" dealers provided the middle range products to contractors, and the "C" dealers handled the homeowner quality tools. In practice, a high-end dealer could get you whatever you wanted- the "C" dealers were likely to be hardware stores, selling to the fellow that wanted to cut a board in half before falling asleep in front of the TV, to paraphrase Eddie Izzard.

We've met the Heavy and Super duty saws, but what of the standard duty?

Left to right: 178 c. 1964,125 c. 1957, 66 c.1959

While the terminology was first introduced in 1956, the original standard duty saw of 1954 was the 125, a 6" saw that, in the words of Porter-Cable's ad department, " includes, at a very low price, many features of professional Porter-Cable saws”.

A Volkswagen Rabbit has the same number of tires as a GTO, but that doesn't really make them equal, now does it?

The 125 isn't a bad saw, really. In fact, it's no worse than most homeowner-level offerings of the time. Our lil' pal is entirely made of very light die castings and features ( if that is the right term) a pivoting base made of stamped steel, an integral thumb lever for opening the lower, telescoping guard, and is a very small, nimble wisp of a circular saw ( 8 lbs, which is impressive in a saw that has no plastic parts other than the brush caps). I'm rather fond of the 125, as it lends itself to sawing at shoulder height or overhead, but there is a distinct East German car feel to this tool; everything feels flimsy in comparison to the reassuring mass of a 528 or BK-10. It's important to recall that the A-6, a saw designed specifically for the home hobbyist, required you to visit at least a "B" dealer, making it a heavy-duty in all but name by the standards of the early '50s ( the A-6 was offered for the first few years of 125 production, but was replaced by the less expensive saw by 1957).

By 1956, the 125 gained a sibling in the 160; a saw that is literally a 125 that ate its vegetables. Bearing a 6 1/2" blade and weighing in at a half pound heavier, the 160 is a bit of apple polishing, offering nothing except a slightly deeper cut and an all ball bearing construction, as opposed to the few bushings in the 125; in fact, the only way to distinguish the difference between the saws is the round cartouche on the upper guard- a 125 has a 6, the 160, a 160.

By 1959, someone at Porter-Cable finally noticed they were making the same saw twice, so the 125 was discontinued, and the 66 was introduced, which is even more like the 160 than the 125 was.

This is called marketing, I understand.

The 66 was a 125, bushings and all, that could accept a 6 1/2" blade, it being known for some time that a 6" saw can't always make it through a two-by-four at a 45-degree angle.

There matters would stay until 1961 when the family expanded- there were no less than four models offered by then, including the new 76, which was a 66 that could count higher, our familiar 160, and two 7" saws, the 170 and 177 ( you guessed it, the 170 had bushings, the 177, all bearings). These three new models had wraparound bases which differed in how they were affixed to the body, but the design was essentially still the same configuration introduced by the departed 125.

The last of the saws germain to our conversation appeared in July of 1962. The Porter-cable/Rockwell lineup included the 170 and 177, but new to the family were the 176 and 178, a 6 1/2" and 8 1/4" saw, respectively. The 176 is, in essence, a 66 with the bronze bushings replaced by needle bearings, but the 178, though notable for being the first P.C. saw to offer an onboard blade lock, represents the limits of how big the design could be made without collapsing like a dying star, and most 178's that have seen much use have upper guards that rattle, as the small rivets holding it in place are nowhere near equal to the task. This would not stop Rockwell from developing one last saw of this lineage, the 592, basically a 160 with a thyroid problem swinging a 10 1/4" blade, which is lunacy. I'd love to find one, if any survive, if only to hold it out in front of me like Yorick's skull and ponder the folly of '60's engineers who must have had someone do their physics homework for them.

Almost forgot: the vital statistics are-

125 : 3,300 rpm, 6" blade, 8 lbs

160:3,500 rpm, 6 1/2" blade, 8 1/2 lbs

66:5,000 rpm, idle ( load speed no longer listed by 1959), 6 1/2" blade,8 1/2 lbs

76:4,500 rpm idle, 6 1/2" blade, 9 1/2 lbs

170:4,500 rpmidle, 7" blade, 9 3/4 lbs

177:4,500 rpm idle, 7" blade, 10 lbs

176:4,500 rpm idle,6 1/2" blade, 10 lbs

178:5,800 rpm idle,8 1/4" blade, 12 lbs

592:5,250 rpm idle,10 1/4" blade,18 lbs

All in all, the vast majority of these saws will still cut to a line, even if they don't exactly inspire confidence in the user. They were the last attempt of the company to offer a low budget tool ,s an area where Porter-Cable never quite found its touch, and on that level, they are interesting.

If, you know, you collect saws like a weirdo.

-James Huston

I own sixty-eight circular saws, and that’s utter lunacy, part five-the heavy/super duties

By the mid-1950s, the Porter-Cable lineup had shifted from the Speedmatic/ Guild dichotomy to a single product line with three designations: standard duty, heavy duty, and super duty ( also known as homeowner duty, contractor duty, and holy cow, you do a lot of sawing duty). Standard duty tools ( 125, 160) are a subject for another time, and we have already seen the heavy duty saws ( A-4,157,146,115,108). Today, we'll discuss the heavy/super duty family.

In 1956, the super duty tribe consisted of some familiar faces; the 507 and 508, BK-10, and BK-12 are all known to us, but a new kid on the block appeared in 1956, a saw that would become an instant classic and herald the further development of new 10" and 12" saws, and go on to a nearly twenty-year career.

Enter the 528.

This example is a type 2. The original, short-lived version ( made, it seems, in the early part of 1956, but already superseded by October of that same year)uses the same K-series handle as the 507/508 saws, complete with an embossed switch plate.

The 528 is, in essence, the logical evolution of the 508, differing in the respects of speed (6,300 rpm no load, versus the 508's 7,000), being an 11 amp saw ( as opposed to the 508 at 9 amps), running an 8-1/4" blade instead of an 8", and of course, the telescoping guard. The swing guard was referred to as a safety guard by the 1950s ( and it is a bit safer when cross-cutting 2"x4" lumber since it doesn't have to move and expose any more of the blade), but it was a bit outdated by the time Ike Eisenhower was winding down his first term. Other companies had already gone to a telescoping system decades ago, and the 115/146/108 saws had proven it to be a perfectly sound system, so the 528 sported the newer design from the beginning. This particular version was heavier than the ones on the 146 and 115 and held up much better; I've had to weld many a 146 guard back together, but I haven't ever seen a 528 guard that was bent, much less broken.